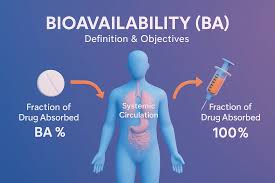

Bioavailability refers to how much of a compound actually reaches systemic circulation and becomes available for the body (or target tissue) to use. It’s one of the most important concepts in pharmacology, drug research, and compound formulation.

Think of it like this:

If you administer 100 mg of a substance, but only 40 mg makes it into circulation, the bioavailability is 40%. The rest is lost through digestion, metabolism, or first-pass liver breakdown.

Key Takeaway

Bioavailability tells you how efficiently a compound is absorbed and used. Higher bioavailability = more effective delivery.

Why Bioavailability Matters

Researchers look at bioavailability for one simple reason: dose does not equal delivery.

Two compounds may share the same milligram amount but behave completely differently once inside the body.

Bioavailability helps determine:

- How much of a compound actually works

- Optimal dosing for research

- Onset and intensity of effects

- Comparisons between oral, sublingual, IV, IM, or transdermal routes

- How quickly a compound is metabolised or cleared

It’s also crucial for understanding why certain compounds seem “weak” or “strong” at similar doses.

How Bioavailability Is Measured

In research, bioavailability is typically expressed as:

Bioavailability (F) = (Amount absorbed / Amount administered) × 100%

Further reading : Bioavailability and Bioequivalence

Modern studies may calculate it using:

- AUC (Area Under the Curve)

- Peak plasma concentration (Cmax)

- Time to peak (Tmax)

- Clearance rate

- Half-life modelling

These help quantify how much compound is truly available to exert a measurable effect.

Further reading : SARMs Half-life

Common Factors That Influence Bioavailability

Bioavailability varies widely depending on:

1. Route of Administration

- IV: 100% (baseline reference)

- Oral: often much lower due to digestion + liver metabolism

- Sublingual: bypasses some first-pass metabolism

- Transdermal: slower but steadier absorption

- Intramuscular/Subcutaneous: moderate to high depending on compound properties

2. Chemical Structure

Some molecules simply absorb better than others.

3. First-Pass Metabolism

The liver breaks down certain compounds aggressively before they reach circulation.

4. Solubility

Poorly water-soluble compounds typically have lower bioavailability.

5. Particle Size & Formulation

Micronisation, salts, esters, and liquid suspensions can dramatically change uptake.

Absolute vs. Relative Bioavailability

Absolute Bioavailability

Comparison of oral vs. IV delivery of the same compound.

Relative Bioavailability

Comparison of two oral formulations (e.g., capsule vs. liquid).

This helps determine which formulation is more efficient.

Bioavailability Example (Simple Visual Table)

| Delivery Route | Typical Bioavailability | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| IV | 100% | Gold standard reference |

| Sublingual | 40–70% | Partially bypasses liver |

| Oral | 10–50% (varies hugely) | Most affected by first-pass metabolism |

| Transdermal | 30–60% | Slow and steady release |

| Intramuscular | 75–100% | Depends on solubility + depot effect |

Why Bioavailability Is Critical in Research

For researchers, bioavailability determines:

- What dose is needed to reach a target concentration

- How frequently the compound should be administered

- Whether oral delivery is feasible or requires alternatives

Check out : Reference grade SARMs

It also helps explain:

- Why two people respond differently to the same dose

- Why increasing dose doesn’t always increase effect linearly

- Why some compounds require higher mg amounts compared to others

In short: bioavailability is the bridge between administering a compound and actually getting results.

Back to SARMS glossary