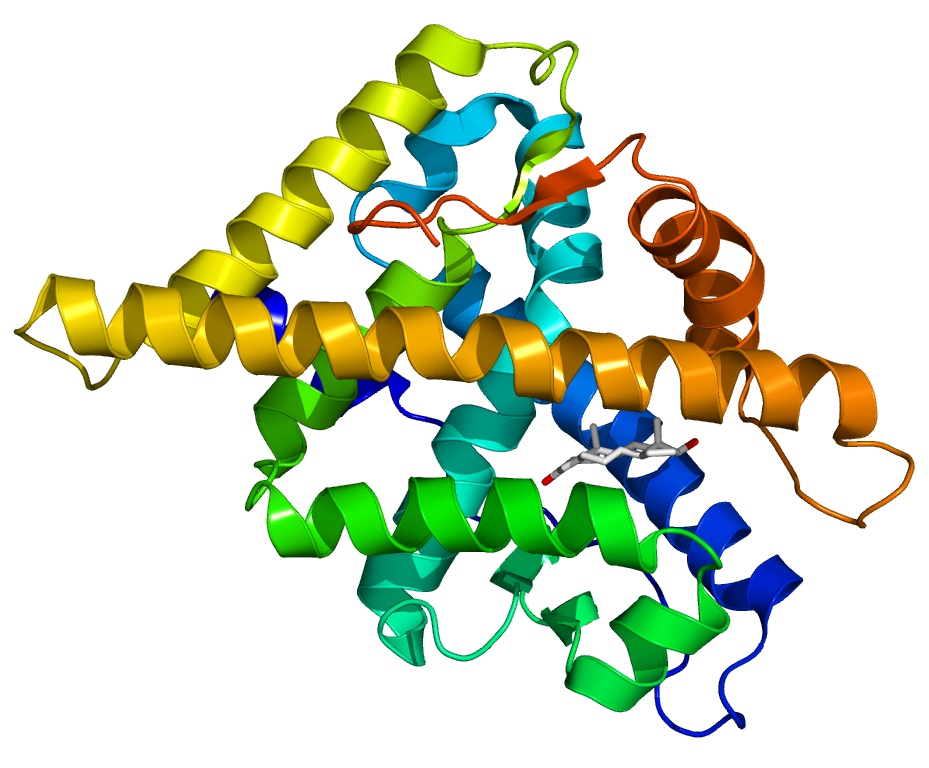

🧬 Androgen Receptor (AR)

Definition:

The androgen receptor (AR) is a type of nuclear receptor — a protein found inside cells that binds to androgens, the body’s natural male sex hormones such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Once activated, it moves into the cell nucleus and switches on genes responsible for muscle growth, strength, and sexual development.

⚙️ How It Works

Think of the androgen receptor as a lock — and hormones like testosterone or DHT as keys.

When an androgen binds to its receptor, this “lock-and-key” interaction triggers a series of genetic events that:

- Stimulate protein synthesis (muscle growth)

- Influence bone density and fat distribution

- Regulate hair growth, libido, and mood

SARMs (Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators) are designed to fit that same lock — but with greater selectivity. Instead of activating androgen receptors throughout the entire body (like anabolic steroids), SARMs can target specific tissues such as muscle or bone, potentially reducing unwanted side effects in other areas.

🧠 Why It Matters in SARM Research

The androgen receptor is at the core of how SARMs work.

Understanding AR behavior helps researchers study how different compounds:

- Bind with varying affinities (strength of interaction)

- Cause distinct transcriptional responses (gene activation patterns)

- Influence muscle hypertrophy, fat loss, and recovery

For example, RAD-140 (Testolone) shows one of the strongest affinities for the androgen receptor among known SARMs, which explains its high anabolic potential in lab studies.

🔬 Scientific Context

- The androgen receptor belongs to the steroid hormone receptor family, which also includes estrogen, glucocorticoid, and progesterone receptors.

- The human AR gene is located on the X chromosome (Xq11-12).

- AR mutations can cause disorders such as androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS).

- Research continues into how AR modulation affects neuroprotection, metabolism, and aging beyond muscle growth.

📜 The History of the Androgen Receptor

The story of the androgen receptor (AR) is a cornerstone in modern endocrinology — a scientific journey that began nearly a century ago and continues to shape how we understand hormones, genetics, and muscle biology today.

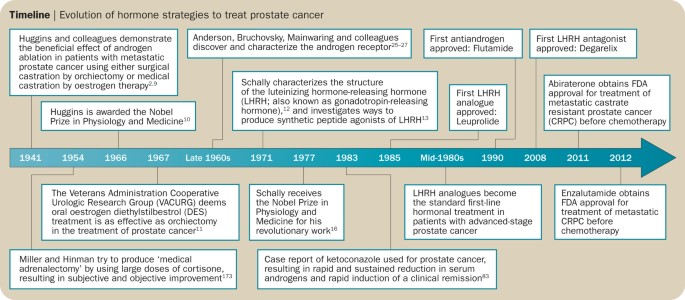

🧩 1940s–1950s: The Hormone Era Begins

In the 1940s, researchers first isolated testosterone and recognized its powerful role in male sexual development and muscle growth. But they didn’t yet know how it worked. The concept of a “receptor” — a cellular target that hormones bind to — was still theoretical. Scientists observed that androgens had tissue-specific effects, hinting that something inside cells was “reading” their signals.

🔬 1960s–1970s: Discovery of the Receptor

In the 1960s, landmark studies using radioactive tracers finally proved that testosterone binds to a specific intracellular protein — the androgen receptor. This was one of the first nuclear receptors ever identified.

By the 1970s, researchers understood that the AR acts as a transcription factor — a protein that moves into the cell nucleus, attaches to DNA, and turns certain genes on or off.

Ostarine was an early compound, and considered to be one of the most prevalent SARMs in history.

This discovery was huge: it explained how hormones could have long-lasting effects by directly altering gene expression rather than just triggering surface signals.

🧬 1980s–1990s: Genetic Insights

The human androgen receptor gene was cloned and sequenced in the late 1980s, revealing its exact location on the X chromosome (Xq11–12).

This breakthrough allowed scientists to link specific mutations in the AR gene to conditions like androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) — where the body produces androgens but cannot respond to them properly.

By the 1990s, the AR had become a model for studying how hormones influence not just physical traits, but also behavior, neurobiology, and aging.

⚗️ 2000s–Today: The SARMs Revolution

The early 2000s introduced a new wave of research — Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs).

These synthetic molecules were designed to selectively activate the androgen receptor in muscle and bone tissue while avoiding unwanted effects in the prostate, liver, or skin.

Pharmaceutical companies like GTx Inc. and Ligand Pharmaceuticals led early trials with compounds such as Ostarine (MK-2866) and RAD-140 (Testolone), aiming to treat muscle wasting, osteoporosis, and hypogonadism. Other compounds, such as MK677, are often grouped into SARMs, although are different entirely.

Although none have achieved FDA approval for medical use, SARM research continues to provide valuable insights into tissue-specific AR modulation — helping scientists understand how to harness the receptor’s benefits while minimizing risks.

⚖️ Research Use Only

Compounds that modulate androgen receptors (SARMs) are not approved for human consumption or therapeutic use.

All products and discussions on this site refer to laboratory research applications only, not medical or dietary use.

🔗 Related Terms

- Selective Androgen Receptor Modulator (SARM)

- Anabolism

- Ligand Binding Affinity

- Transcriptional Activation

- Testosterone

💬 FAQ

What is the main function of the androgen receptor?

It acts as a molecular switch that turns on genes responsible for muscle and tissue growth when bound by hormones like testosterone.

How do SARMs interact with androgen receptors?

They selectively bind to ARs in muscle and bone tissue, aiming to mimic anabolic effects with fewer androgenic side effects compared to steroids.

Can androgen receptors be “upregulated”?

Yes — prolonged exercise, certain hormonal states, and pharmacological modulation can increase AR density, but mechanisms vary.