💪 Anabolic

Definition:

Anabolic refers to any biological process that builds up complex molecules from simpler ones — the opposite of catabolic, which breaks things down.

In the context of physiology and sports science, “anabolic” typically describes the growth and repair of muscle tissue, bone density, and other body structures through increased protein synthesis and cellular regeneration.

⚙️ The Science Behind “Anabolic”

At its core, anabolism is about construction.

When the body’s anabolic processes are active, it’s in a growth state — using energy to create new tissues, enzymes, and hormones.

Key anabolic pathways involve:

- Protein synthesis – converting amino acids into muscle fibers.

- Glycogen storage – building energy reserves in muscles and liver.

- Bone mineralization – increasing bone strength and density.

- Cellular repair – restoring tissues after exercise or injury.

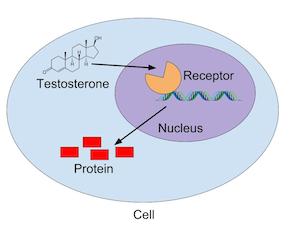

Hormones like testosterone, insulin, and growth hormone (GH) play leading roles in driving these anabolic reactions.

🧬 Anabolic vs. Catabolic

To understand anabolism, you need its counterbalance — catabolism.

- Anabolic = build up (For example, SARMs are anabolic. Muscle, tissue, energy stores)

- Catabolic = break down (muscle, glycogen, fat for energy)

The body constantly shifts between these states. A post-workout recovery phase, for example, is anabolic, while fasting or high-intensity training temporarily increases catabolic activity.

Maintaining a healthy balance between the two is key to recovery, performance, and longevity.

⚗️ What Makes a Compound “Anabolic”?

A compound is described as anabolic if it stimulates tissue growth — especially muscle — by activating androgen receptors or other anabolic signaling pathways.

Examples include:

- Anabolic steroids – synthetic derivatives of testosterone that broadly activate androgen receptors.

- SARMs (Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators) – research compounds designed to selectively trigger anabolic effects in muscle and bone while minimizing androgenic side effects in other tissues.

Both act through similar mechanisms but differ in tissue selectivity and safety profiles under study.

🧠 Why It Matters in SARM Research

The term “anabolic” defines what SARMs are meant to achieve — anabolic effects without full androgenic impact.

In laboratory research, this means studying how selective receptor modulation can:

- Enhance muscle protein synthesis

- Prevent muscle wasting in animal models

- Support bone regeneration

📜 The History of “Anabolic”

The word anabolic has ancient linguistic roots but a modern scientific story — one that runs parallel to the rise of endocrinology, hormone research, and sports science.

🧩 Ancient Roots, Modern Meaning

The term comes from the Greek ἀναβολή (anabolē), meaning “a raising up” or “to build up.”

In early physiology texts of the 19th century, “anabolism” was used to describe constructive metabolism — processes that built tissue and stored energy, as opposed to “catabolism,” which broke things down.

By the early 1900s, scientists like Sir Edward Schäfer and Ernest Starling (who helped define “hormone”) used anabolic to describe how internal chemical messengers could promote tissue growth.

⚗️ 1930s–1950s: The Hormone Revolution

The true anabolic era began in the 1930s, when researchers first isolated and synthesized testosterone.

This discovery transformed physiology — it proved that a single molecule could dramatically increase nitrogen retention and muscle mass.

By the 1950s, synthetic derivatives of testosterone — the first anabolic steroids — were developed for medical purposes such as treating muscle wasting and hypogonadism.

The word anabolic quickly became synonymous with muscle growth and performance enhancement, entering both medical and athletic vocabularies.

🧬 1960s–1990s: From Steroids to Selectivity

As scientists mapped hormone receptors in the 1960s and 1970s (including the androgen receptor), it became clear that anabolic effects came from specific gene activation patterns — not just hormone levels.

This shifted research toward finding compounds that could separate anabolic benefits from androgenic side effects.

The quest led to decades of pharmaceutical research — culminating in the 1990s discovery of SARMs (Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators).

These were designed to deliver anabolic effects to muscle and bone, without triggering unwanted hormonal responses elsewhere.

🧠 Modern Context

Today, anabolic remains a central concept in everything from sports medicine and molecular biology to anti-aging research.

It’s not just about muscle anymore — anabolic pathways influence tissue regeneration, bone remodeling, and even neural protection.

In research settings, understanding anabolism helps scientists explore safer, tissue-selective methods to promote growth and recovery — the same scientific frontier that gave rise to SARMs and continues to drive metabolic and longevity studies today.

Understanding anabolic pathways helps researchers design compounds that separate beneficial effects (growth, repair) from unwanted ones (hormonal imbalance, prostate enlargement).

⚖️ Research Use Only

Compounds exhibiting anabolic properties are not approved for human consumption or medical use.

All research should be performed by qualified professionals in controlled laboratory environments.

💬 FAQ

What does “anabolic” literally mean?

It comes from the Greek anabole, meaning “to build up.” In biology, it describes any energy-using process that constructs molecules or tissues.

Are SARMs anabolic?

Yes — SARMs are designed to produce anabolic effects (muscle and bone growth) by selectively binding to androgen receptors in certain tissues.

What’s the difference between anabolic and androgenic?

Anabolic refers to growth-promoting effects like muscle development; androgenic refers to masculinizing effects such as facial hair or voice deepening.

📚 References

- Hall, J.E. Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. Elsevier, 2020.

- Nader, G.A., & Esser, K.A. (2001). “Intracellular signaling specificity in skeletal muscle hypertrophy.” Journal of Applied Physiology, 90(2), 855–863.

- Basaria, S. (2010). “Androgen abuse in athletes: Detection and consequences.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 95(4), 1533–1543.

- Dalton, J.T., & Taylor, R.P. (2016). “Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators: Concept and Development.” Endocrine Reviews, 37(5), 710–738.